This post provides extended discussion of and references for my poster-based talk given at the INSIGHT 2021 conference on September 10, 2021. My commentary published in Psychopharmacology also discusses some of these same issues and provides concrete suggestions for future research. This is a work in progress and may evolve over time.

2021-09-10 Samuli Kangaslampi, samuli@kangaslampi.net

Increasing evidence suggests that consuming psychedelic substances in some contexts may have therapeutic effects for some people. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression has entered Phase 2 clinical trials (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021). Meanwhile, experimental, survey-based, and register-based studies suggest links between psychedelic consumption and some areas of well-being (e.g., Agin-Liebes et al., 2021; Jiménez-Garrido et al., 2020; Hendricks et al., 2015; Simonsson et al., 2021; Uthaug et al., 2019). In order to better understand and maximize possible therapeutic effects, it would be very useful to know how, through which psychological mechanisms, psychedelics or psychedelic-assisted therapy may have beneficial outcomes.

Indeed, research on the psychological mechanisms of the effects of psychedelics is increasing. A number of recent publications have suggested various mechanisms and pathways for beneficial effects (e.g., Davis et al., 2020, 2021; Forstmann et al., 2020; Kettner et al., 2021; van Mulukom et al., 2020, Roseman et al., 2018; Thiessen et al., 2018; Zeifman et al., 2020). However, there are some problems and pitfalls in approaches several recent studies have taken to analyzing such mechanisms. Many of these problems and unstated assumptions in mechanism research have previously been pointed out and discussed in other areas of research, especially psychotherapy and social psychological research. Here, I discuss the value, challenges, and best practices of providing convincing evidence for the psychological mechanisms of the possible therapeutic effects of psychedelics.

The question of mechanisms, of how interventions, exposures, or other causes have effects on final outcomes we are interested in, has a long history in many areas of psychological science, especially psychotherapy and social psychological research. This is understandable, because understanding mechanisms is useful for many different reasons. For instance, in the context of psychological interventions, Kazdin (2007) pointed out six benefits: 1) Research on mechanisms can help us optimize treatments, to know what to focus on in treatment, what processes we should especially target and trigger; 2) Understanding how treatments work helps us translate research into real-life clinical practice, and ensures generalizability of effects without diluting essential change processes, and may assist in dissemination and adoption; 3) Understanding (transdiagnostic) mechanisms can help us understand the diversity of outcomes of interventions, the links between what happens in treatment and how many different outcomes may change; 4) Identifying common mechanisms that different treatments work by can bring parsimony and clarity to the many different psychotherapies and interventions in use and development; 5) By uncovering mechanisms, we may also recognize moderators of treatment effectiveness and help predict who may benefit and under which circumstances; and 6) Mechanisms identified may have relevance for our understanding of people’s functioning and well-being beyond therapy. Most of these motivations certain also apply to psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted therapy.

As analyses of mechanisms are so popular, many commentaries, reviews, and instructive articles have been written about how to best study psychological mechanisms (e.g, Bullock et al., 2010; Hayes & Rockwood, 2017: Kazdin, 2009; Pek & Hoyle, 2016; Tryon, 2018). These publications also include much guidance and critique relevant to research on psychedelics, which I draw upon below.

Research on psychological mechanisms as relates to psychedelics is in its early stages. We should not expect perfect study designs or definite answers from the first analyses being carried out in this field. Even imperfect designs can certainly provide useful evidence. The somewhat unusual topic of interest, psychedelics, also introduces several additional challenges to the already challenging pursuit of identifying mechanisms and pathways of action. However, I think it would be important to try and set this area of research on a solid path from the start, with agreed upon good research practices and carefully considered analyses. Looking at some of the recent studies published in this area, it is apparent that there are some common problems, unstated assumptions, and pitfalls in the approaches that they have taken. Luckily, most of these problems can be solved, and even more useful, considered research can be done in the future.

Context and mechanisms – moderators and mediators

The first issue I note is some confusion in or at least atypical usage of terminology in some recent publications (e.g., Netzband et al., 2020; Roseman et al., 2018, 2019). In several areas of psychological research, and indeed in other fields of science, too, so-called third variables have been divided into several distinct categories (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). Mechanisms, as processes or events transmitting or mediating the effects of a cause on an outcome, are typically modeled and studied as mediators. Meanwhile, we may often also be interested in factors (variables) that change how the cause affects the outcome, that modulate or moderate the effects of the cause on the outcome, but do not mediate it. Such factors or variables are modeled and studied as moderators. There may also be other third variables included in analyses, such as covariates or confounders.

While the statistical tools and formulae used to analyze them are often very similar, I believe especially the moderator-mediator distinction is useful and important and would hope that the emerging field of psychedelic research sticks to this fairly clear tradition of naming third variables (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017; Kraemer et al., 2002). Most importantly, while moderators may affect the outcome (in interaction with the cause and independently), they represent things the cause does not affect or change. Meanwhile mediators (some of which may represent mechanisms) are by definition things that the cause affects and that then affect the outcome, which transmit some of the cause’s effects on the outcome. Accordingly, things like demographic and other background variables relating to the participant; the physical, social, and psychological state in which ingestion takes place; preparation, intention, and therapeutic alliance etc. are important potentially moderating factors to take into consideration. But they are set beforehand, not affected by the ingestion of the psychedelic, and thus appropriately thought of as moderators, not mediators.

Beyond clearly separating mechanisms (studied as mediators) from contextual factors (studied as moderators), I would suggest being even more clear about whether we are studying processes or events that take place during acute psychedelic effects or changes or processes that extend beyond the acute effects. Both may be thought of as mechanisms that mediate the effects of psychedelics on different outcomes. I have suggested calling the former acute mechanisms and the latter post-acute mechanisms. This terminology may not be optimal, and perhaps better suggestions will come forward.

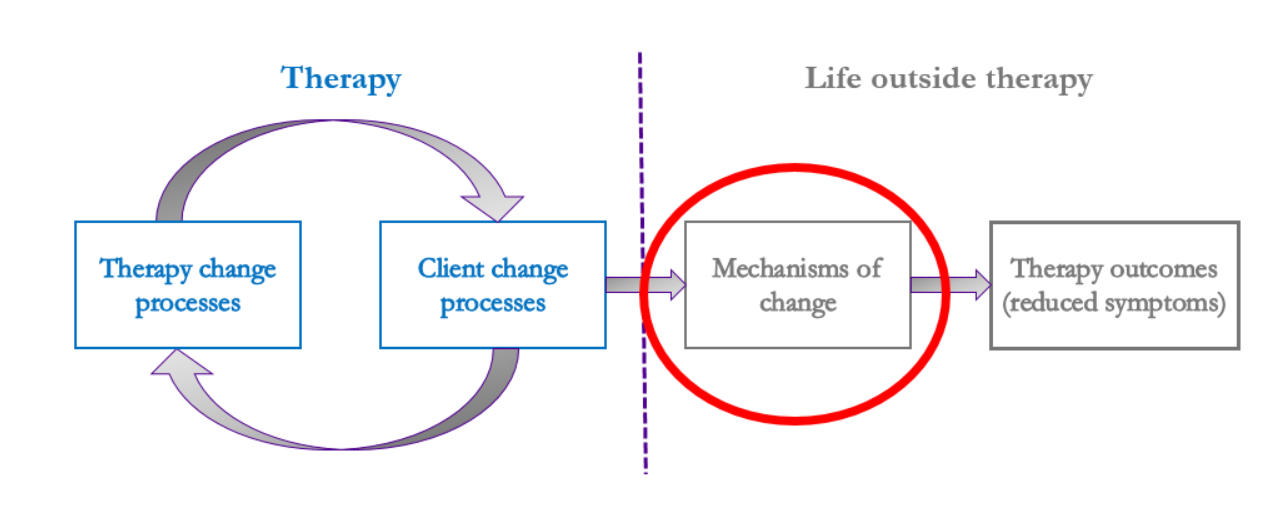

If we limit our discussion to psychedelic-assisted therapy, another way of thinking about change processes and mechanisms is to separate what happens within the intervention from what happens outside it in the client or participant’s life generally. When studying the psychological mechanisms of psychological interventions for PTSD (without psychedelics), I found it helpful to ground my research in a framework offered by Brian Doss (2004), illustrated below. He divided what happens in psychological treatment into change processes taking place within the therapeutic sessions and context, and change mechanisms or mechanisms of change extending outside it. Using this framework, post-acute mechanisms of psychedelic-assisted treatment would be considered mechanisms of change that have generalized into the client’s life beyond the psychedelic session and associated therapy. In other words, they represent changes in the client’s thinking, beliefs, emotions, behavior, social relations or other areas that were caused by the psychedelic exposure and in turn have lead to or continue to result in changes in the desired final outcomes, such as reduced symptoms or improved well-being. Acute mechanisms would be more like client change processes that occur within the context of or inside the therapy or intervention.

The promise and challenges of mediation analysis

Mechanisms can be studied with a variety of different approaches and study designs, but a direct and fairly simple way, which several recent publications on psychedelics have also employed, is using mediation analysis. Mediation analysis is a statistical approach often used to provide evidence about the roles of particular mechanisms in changes in final outcomes. Mediation analyses allow us to examine and quantify indirect effects of causes on outcomes via mediators, in this case variables thought to represent mechanisms we are interested in. Usually, mediation analysis are carried out within a single set of data, although meta-analytic approaches are also possible.

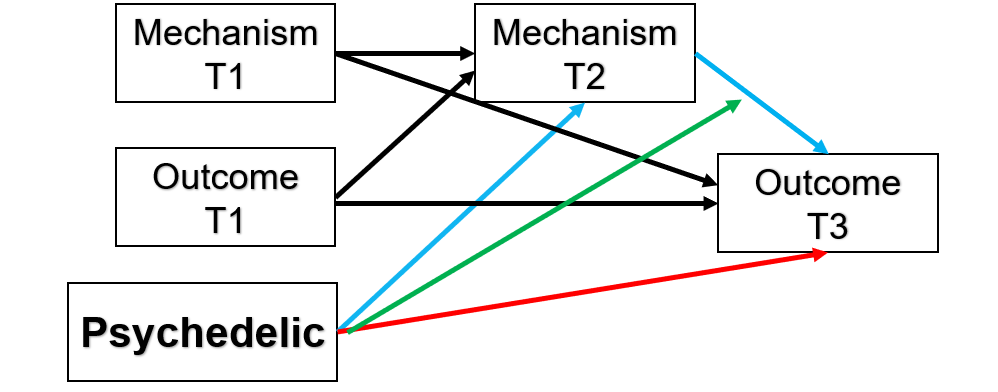

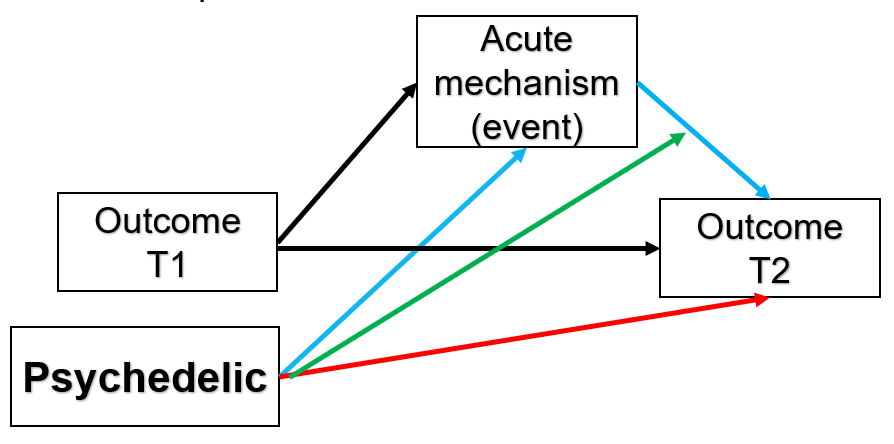

Mediation analyses are usually accompanied by graphs illustrating the mediation model proposed and estimated. Mediation models can take many shapes and forms, and can sometimes be quite complicated, but a couple of simple examples are presented below. In modern mediation analysis, we are typically interested in the statistical significance and strength of the indirect effect, which is depicted in blue.

One issue that is immediately apparent from looking at graphs of mediation models is that they always include directed arrows. Presenting such directed models, as well as the language used to describe the results of mediation analyses (e.g., “M mediates the effects of X on Y.”) mean that mediation analyses may be considered inherently causal (Nguyen et al., 2020). When we draw an arrow from X to Y (via M), instead of from Y to X, clearly we are suggesting that we have some basis or reasoning to claim that X is causing Y, instead of Y causing X, or them being associated without causing each other. This is is contrast to merely presenting correlational analyses and talking about covariance, correlation, or associations.

Most recent publications on mechanisms of the effects of psychedelics employ mediation analysis, but simultaneously explicitly deny studying causal processes. They present graphs with arrows and talk about processes mediating the effects of psychedelics on final outcomes, but several point out in the limitations of the study that causal interpretations cannot be made based on their analyses. I find this approach problematic and believe that researchers would do best to decide from the get go whether they are attempting to study and find evidence for causal (mediated) effects, or whether they are simply studying associations, and stick with this decision throughout. Otherwise, they risk their findings being taken for more than they are. Although researchers themselves are likely to be aware of the limitations of their data and analyses, the way their results are later used in further research, not to mention presented in the media and other outlets, rarely takes into account caveats presented in Limitations sections. Instead, if researchers (in their titles or conclusions) claim to have shown mediation of effects, this is taken seriously and taken as evidence of causal effects.

We do often wish to study causal effects mediated by some mechanism, and for this, mediation analysis is a great tool. However, for mediation analysis to provide evidence for causal effects, there are number of assumptions that must be fulfilled (Kraemer et al., 2002; Preacher, 2015; Nguyen et al., 2020). These assumptions have typically not been made explicit in recent publications on psychedelics. The key assumption is that the model presented is in fact correct. This means that the relations between constructs have been modeled correctly, the suggested temporal order of effects is correct, errors are negligible or accounted for, and that no relevant omitted influences are missing.

As regards possible omitted influences, in controlled research, especially randomized experiments, we can be fairly confident that there are no unmeasured confounders in the cause-mechanism and and cause-outcome relations. In other types of research, we should have other good grounds for assuming that the cause really caused (all of the) changes in the mechanism and outcome, i.e., that there are no unmeasured confounders in these relations. However, even in randomized experiments, concerns about unmeasured confounding in the mechanism-to-outcome relation remain. We need to think carefully about what confounders, variables that affect both the mechanism and outcome, or that correlate with the mechanism and affect the outcome, might exist. Any such omitted variables will bias our findings, overstating the degree of mediation through the mechanism (Bullock et al., 2010). This problem is even more pronounced in analyses that incorporate several mediators in sequence (as in Forstmann et al., 2020; van Mulukom et al., 2020), as there are many more relations that could include unmeasured confounders.

The issue of mechanism-outcome confounding is difficult to fully address in any study design, but at the very least researchers should explicitly state that no unmeasured confounding in the mechanism-outcome relation is assumed and consider whether that assumption is realistic. Some solutions do exist, such as randomizing for the mechanism or allowing it to operate in some subjects and not in otherwise (typically very difficult for psychological mechanisms), using sensitivity analyses and particular statistical tools (MacKinnon & Pirlett, 2015; Preacher, 2015), or demonstrating the causal effect of the mechanism on the outcome or the specificity and consistency of the mediated effect in other solid studies.

One assumption of the so-called traditional psychological mediation analysis approach that has received quite a bit of attention in the mediation analysis literature in other fields, but none in psychedelic research, is the possibility of cause X mechanism interaction on outcomes. As far as I can tell, the possibility that the cause (e.g., ingesting a psychedelic, or having a mystical experience) might change the way the suggested mechanism (e.g., increased social connectedness, increased psychological flexibility) affects the final outcome (e.g., mental well-being) has not been accounted for in any of the published research. The traditional psychological mediation analysis approach foregoes this possibility, but it can easily be analyzed, and other approaches to mediation do include it (Kraemer et al., 2008; Nguyen et al., 2020).

There could be a number of possible sources of cause X mechanism interaction, when we study the effects of psychedelics. For example, psychedelic ingestion could affect how participants interpret and answer questions measuring the mechanism (say, social connectedness) and outcome (say, mood), affecting their relationship. Low variability in the experience of an acute mechanism such as a mystical experience in a control group, while there is high variability in the intervention group may also affect the mechanism-outcome relation. MacKinnon et al. (2020) provide a good list of possible sources of interaction to consider. In any case, I would certainly suggest that researchers take this possibility into account, and study whether such interaction effects appear to be present. In the above mediation model graphs, this is illustrated in green.

Perhaps the most crucial question many of the published studies fail to address is the temporal order of effects. The suggested mediation model being correct rests fundamentally on this issue. If we can show that the cause first caused (changes in) the mediator, and that this mediator then, that is, later, caused changes in the outcome, we may have good evidence for a mediated causal effect. However, in many if not most, recent publications, this temporal order has not been demonstrated. Some have relied on fully cross-sectional data, where it is typically not even possible to demonstrate that the cause (psychedelics) lead to changes in the outcome, let alone that a mediated, indirect effect is present (e.g., Thiessen et al., 2018). Others do have some basis for saying that changes in the outcome took place from before ingestion to after ingestion of a psychedelic, but still cannot say anything about whether changes in the mechanism preceded changes in the outcome (e.g. Davis et al., 2020, 2021). The study by Kettner et al. (2021) about psychedelic communitas and its direct and mediated effects on psychological well-being is a notable exception with five points of measurement.

When we cannot show the temporal order of changes in mechanism and outcome, it is in most cases equally possible that the change in outcome lead to the change in suggested mechanism. It is also possible that the change in outcome was a simultaneously occurring side effect. For instance, Forstmann et al. (2020) suggest and present in their mediation analysis that increased social connectedness would be a mechanism through which psychedelic use improves mood. However, they measured both social connectedness and mood once and simultaneously. Accordingly, there is nothing in their data that could separate a social connectedness–>mood effect from a mood–>social connectedness, provided there is any effect at all. Further, they did not establish that mood or social connectedness even changed in the first place. Similarly, in their study, van Mulukom et al. (2020) suggest that their findings based on a mediation model using cross-sectional survey data “provide support for the hypothesis that psychedelics can positively affect narcissistic personality traits, through their awe-inducing potential”. However, the data appear to be in equal concordance with the interpretation that more narcissistic people are less prone to awe experiences when taking psychedelics. Such alternative interpretations should, at a minimum, be recognized and considered.

To study post-acute mechanisms in a way that demonstrates the temporal order of changes, a minimum of three points of measurement are necessary (before, after, later). Even more measurements are of course preferable and allow for more precise modeling of longitudinal processes (as in Kettner et al., 2021). When several measurements of both post-acute mechanisms and outcomes are available, we can perform model comparisons and be much more confident about our findings. For acute mechanisms, we can be sure that they took place during the acute effects, so two points of measurement may suffice (before and after for the outcome, [preferably immediately] after for the acute mechanism), although more are still preferable.

Beyond the model being correct, using cross-sectional data is also a problem for the estimates of indirect effects we end up with. Even if the assumed temporal order of effects is indeed correct, using cross-sectional data can bias our estimates of longitudinal effects in unpredictable ways. This was pointed out most forcefully by Maxwell et al. (2011) who state “a given pattern of cross-sectional correlations can arise from very different combinations of underlying longitudinal parameters. As a result, any attempt to infer the properties of the underlying longitudinal process on the basis of the cross-sectional parameters is almost certainly futile.” (Maxwell et al., 2011) While I would perhaps not be quite this pessimistic, I would suggest that when researchers only have cross-sectional data available with no basis for assuming the order of changes or effects, they should refrain from mediation analyses and just study and report associations. Later studies can then confirm the hypotheses such correlational research suggests.

A more technical issue in mediation analyses is how mediation is demonstrated and quantified. In the past, stepwise approaches to proving mediation exists were popular (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Somewhat more recently, the Sobel (1982) test emerged as a one-step approach. However, the traditional form of the Sobel test relies on an assumption of normality for the indirect effect (a product of two random variables), which is unrealistic, so today, it is recommended to use bootstrapping to study the significance of the indirect path (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013; MacKinnon, 2002). For quantifying how large the mediated effect is, we may use fully or partially standardized regression estimates, depending on the nature of the causal variable. Other effect size estimates have also been developed (e.g., Lachowicz et al., 2018). “Percentage mediated” estimates are sometimes presented, dividing the indirect effect by the total effect, but can be problematic as they could reach over 100% when there are different indirect effect in opposite directions.

One idea that I believe should be abandoned is using the statistical significance of the remaining direct path (presented in red in Figures 2 and 3) to determine whether the effect was completely or fully mediated (as in Davis et al., 2020 and Kettner et al., 2020). The change from statistical significance to non-significance for a direct path when the indirect path is added may result from a tiny change in the estimate itself (as in, e.g., Thiessen et al., 2018), hardly good evidence for “full” mediation. If researchers are truly interested in whether the remaining direct effect is zero, other criteria, such as the confidence interval of the direct effect or equivalence tests that it is zero, should be considered.

In recent years, causal mediation analysis has appeared as an alternative to the so-called traditional psychological mediation analysis approach (Nguyen et al., 2020). The causal mediation analysis approach calls for explicit, careful causal thinking before we engage in the actual analyses, specifying more exactly the effects we are pursuing, and noting the assumptions under which our findings are proof for causal effects (Imai et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2020). I would recommend all researchers in psychedelic research and beyond interested in studying mechanisms to familiarize themselves with this approach grounded in the counterfactual framework of causal analysis (Pearl, 2000, 2001). MacKinnon et al. (2020) have noted that many of the traditional mediation analyses can be seen as special cases in this more widely applicable causal mediation analysis framework, with the key difference being the exclusion/inclusion of the possibility of cause X mechanism interaction.

Mediation analysis can be a powerful and useful tool, but it is only a tool, and one that presents some demands for the quality of the data that we need to have and one that makes assumptions we need to be aware of. Implementing and presenting mediation models is straightforward. If we take cross-sectional or otherwise inadequate data, draw graphs of a mediation model and show that an indirect path is significant, we may end up with an analysis that is convincing at first glance and allows us to tell an engaging story about, e.g., how psychedelics lead to improved well-being. But too often the only reason the arrows and claimed directed effects are there in our analyses is because we put them there. We must be careful not to fool ourselves or others into thinking that we have proved or provided evidence for something we have not. When researchers are not setting out to study causal processes, or do not have the data to do so, it would be best to not present mediation analyses. Exploratory studies about associations are fine, too.

From mediators to mechanisms

Going beyond the specifics of mediation analyses, there are some other issues to consider in identifying and studying the psychological mechanisms of psychedelics. First, where should we look to find some mechanisms? It is commonplace in psychological research that all good things or developments correlate with all other good things, and all bad things correlate with all other bad things. Studying and providing evidence for fairly obvious correlations between aspects of beneficial progress in related areas may not be very worthwhile. So what makes for a good mechanism to study?

Mechanisms should be non-trivial in that they have potential explanatory value and are theoretically sensible and/or empirically supported (Johansson and Høglend 2007). Accordingly, the search for mechanisms should not be ad hoc or capitalize on chance findings. Exploratory research certainly has value, and it’s worth reporting all possible correlations and even surprising connections for future study. But for research explicitly trying to provide evidence for the causal role of a mechanism in an outcome, the mechanisms studied should be decided beforehand based on theory or previous research. In the case of psychedelic-assisted treatment, such previous research could include, e.g., neurobiological findings about psychedelics, research on the mechanisms involved in non-psychedelic treatments, or earlier exploratory research. Studying meaningful potential mechanisms that psychedelic ingestion or the psychedelic-assisted treatment in question is specifically not expected to draw on for its effects may also be valuable (Kazdin 2007) to reinforce arguments for another mechanism’s specific role. Several potential mechanisms may be studied simultaneously and included in the same models.

In any case, preregistration of the planned analyses and hypotheses is especially important for mechanism research. In the context of controlled trials, it would be important for researchers to include plans for studying psychological mechanisms in the original protocols and preregistrations prepared before commencing a study. But preregistration has great value in observational, naturalistic, survey-based, and register-based research as well.

Further, mechanisms should be sufficiently distinct from both the cause and the outcome. Studying a mechanism that simply reflects a part of the treatment, for instance, will not tell us much about how the treatment works. Similarly, if the mechanism is just another aspect of the outcome, showing that changes in it lead to changes in the total outcome is not very informative.

When studying the mechanisms of the effects of some cause on some final outcome, we also need to think carefully about how to define and operationalize the cause. In the context of psychedelics, the most straightforward approach is to study exposure to / ingestion of a psychedelic vs. no exposure/ingestion. This is the usual starting point for controlled research, and can also be used in non-controlled research, especially if it is prospective. Alternatively, the level of dosage of the psychedelic might be considered as the cause. A number of studies have also taken particular effects of psychedelic ingestion as the cause they are studying, e.g., mystical experience or insight experiences (Davis et al., 2020; 2021.) or a sense of communitas acutely experienced (Kettner et al., 2021). It is also sometimes not obvious what the precise outcome that the mechanism relates to should be. Even if our interest is set on a particular phenomenon, say depression, we can model it as an outcome in many different ways (e.g., with a clinical cut-off or as continuous level of symptoms) and over many different time frames (e.g., immediate vs. long-term changes).

It is also worth noting that the effects of psychedelics on outcomes like depression appear to be very rapid. It may be difficult to identify psychological mechanisms of such rapid or immediate effects. In many cases it might make more sense to try and identify the (post-acute) psychological mechanisms that maintain good mental health or keep away mental health symptoms that psychedelics have quickly reduced. In that case, the outcome to be studied would be change in the mental health variable from the immediate post-acute phase to a longer-term follow-up, while the mechanism would be change in the psychological process from before to after psychedelic ingestion.

A program of research

In the end, even when carefully planned and carried out, individual studies can only reveal so much about the mechanisms by which psychedelics may have therapeutic effects. For conclusively demonstrating mechanisms, we will probably need other studies, too, especially to show causality in the mechanism to outcome relation. Besides showing that mediation occurs with a statistical analysis, for a mechanism to be useful, we also need to try and explain how, through which steps, the suggested mechanism is able to transmit effects on the outcome in question. There is always room for more micro-level analyses. We will also need to demonstrate a specific and consistent role for the mechanism over several studies in different populations. All this suggests that the final answer to identifying and providing convincing evidence for the psychological mechanisms that psychedelics tap into for their therapeutic effects will require a larger program of research. Luckily, it looks like such a program is now getting started.

References

Agin-Liebes, G., Haas, T. F., Lancelotta, R., Uthaug, M. V., Ramaekers, J. G., & Davis, A. K. (2021). Naturalistic Use of Mescaline Is Associated with Self-Reported Psychiatric Improvements and Enduring Positive Life Changes. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsptsci.1c00018

Bullock, J. G., Green, D. P., & Ha, S. E. (2010). Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (Don’t expect an easy answer). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 550–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018933

Carhart-Harris, R., Giribaldi, B., Watts, R., Baker-Jones, M., Murphy-Beiner, A., Murphy, R., Martell, J., Blemings, A., Erritzoe, D., & Nutt, D. J. (2021). Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(15), 1402–1411. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032994

Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., & Griffiths, R. R. (2020). Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.004

Davis, A. K., Xin, Y., Sepeda, N. D., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Williams, M. T. (2021). Increases in Psychological Flexibility Mediate Relationship Between Acute Psychedelic Effects and Decreases in Racial Trauma Symptoms Among People of Color. Chronic Stress, 5, 247054702110356. https://doi.org/10.1177/24705470211035607

Doss, B. D. (2004). Changing the way we study change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(4), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph094

Forstmann, M., Yudkin, D. A., Prosser, A. M. B., Heller, S. M., & Crockett, M. J. (2020). Transformative experience and social connectedness mediate the mood-enhancing effects of psychedelic use in naturalistic settings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(5), 2338–2346. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918477117

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The Relative Trustworthiness of Inferential Tests of the Indirect Effect in Statistical Mediation Analysis: Does Method Really Matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613480187

Hendricks, P.S., Thorne, C.B., & Clark, C.B. (2015) Classic psychedelic use is associated with reduced psychological distress and suicidality in the United States adult population. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29, 280–288.

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

Jiménez-Garrido, D. F., Gómez-Sousa, M., Ona, G., Dos Santos, R. G., Hallak, J. E. C., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á., & Bouso, J. C. (2020). Effects of ayahuasca on mental health and quality of life in naïve users: A longitudinal and cross-sectional study combination. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 4075. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61169-x

Johansson, P., & Høglend, P. (2007). Identifying mechanisms of change in psychotherapy: Mediators of treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.514

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802448899

Kettner, H., Rosas, F. E., Timmermann, C., Kärtner, L., Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Roseman, L. (2021). Psychedelic Communitas: Intersubjective Experience During Psychedelic Group Sessions Predicts Enduring Changes in Psychological Wellbeing and Social Connectedness. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 623985. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.623985

Kraemer, H. C., Wilson, G. T., Fairburn, C. G., & Agras, W. S. (2002). Mediators and Moderators of Treatment Effects in Randomized Clinical Trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 877. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877

Kraemer, H. C., Kiernan, M., Essex, M., & Kupfer, D. J. (2008). How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology, 27(2suppl), S101–S108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101

Lachowicz, M. J., Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2018). A novel measure of effect size for mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 23(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000165

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

MacKinnon, D. P., & Pirlott, A. G. (2015). Statistical Approaches for Enhancing Causal Interpretation of the M to Y Relation in Mediation Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314542878

MacKinnon, D. P., Valente, M. J., & Gonzalez, O. (2020). The Correspondence Between Causal and Traditional Mediation Analysis: The Link Is the Mediator by Treatment Interaction. Prevention Science, 21(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01076-4

Maxwell, S. E., Cole, D. A., & Mitchell, M. A. (2011). Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation: Partial and Complete Mediation Under an Autoregressive Model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(5), 816–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.606716

van Mulukom, V., Patterson, R. E., & van Elk, M. (2020). Broadening Your Mind to Include Others: The relationship between serotonergic psychedelic experiences and maladaptive narcissism. Psychopharmacology, 237(9), 2725–2737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05568-y

Netzband, N., Ruffell, S., Linton, S., Tsang, W. F., & Wolff, T. (2020). Modulatory effects of ayahuasca on personality structure in a traditional framework. Psychopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05601-0

Nguyen, T. Q., Schmid, I., & Stuart, E. A. (2020). Clarifying causal mediation analysis for the applied researcher: Defining effects based on what we want to learn. Psychological Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000299

Pearl, J. (2000). Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge University Press

Pearl, J. (2001). Direct and indirect effects. In J. Breese & D. Koller (Eds.), Proceedings of the 17th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 411–420). San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Pek, J., & Hoyle, R. H. (2016). On the (In)Validity of Tests of Simple Mediation: Threats and Solutions: (In)Validity of Tests of Simple Mediation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(3), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12237

Preacher, K. J. (2015). Advances in Mediation Analysis: A Survey and Synthesis of New Developments. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 825–852. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015258

Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Idialu-Ikato, K., Kaelen, M., Watts, R., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2019). Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: Validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1076–1087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119855974

Roseman, L., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). Quality of Acute Psychedelic Experience Predicts Therapeutic Efficacy of Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00974

Simonsson, O., Sexton, J. D., & Hendricks, P. S. (2021). Associations between lifetime classic psychedelic use and markers of physical health. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 026988112199686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881121996863

Sobel, M.E. (1982) Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Thiessen, M. S., Walsh, Z., Bird, B. M., & Lafrance, A. (2018). Psychedelic use and intimate partner violence: The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 32(7), 749–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118771782

Tryon, W. W. (2018). Mediators and Mechanisms. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(5), 619–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618765791

Uthaug, M. V., Lancelotta, R., van Oorsouw, K., Kuypers, K. P. C., Mason, N., Rak, J., Šuláková, A., Jurok, R., Maryška, M., Kuchař, M., Páleníček, T., Riba, J., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2019). A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness-related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology, 236(9), 2653–2666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05236-w

Zeifman, R. J., Wagner, A. C., Watts, R., Kettner, H., Mertens, L. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2020). Post-Psychedelic Reductions in Experiential Avoidance Are Associated With Decreases in Depression Severity and Suicidal Ideation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 782. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00782